WordPress Blogs: Articles, Bibliographies, Media

Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji (富嶽三十六景 Fugaku Sanjūrokkei) is a series of landscape prints by the Japanese artist Hokusai (1760–1849). The series depicts Mount Fuji from different locations and in various seasons and weather conditions. The series was produced from 1830 to 1832, when Hokusai was in his seventies and at the height of his career. Among the prints are three of Hokusai’s most famous: The Great Wave off Kanagawa; South Wind, Clear Sky; and Rainstorm Beneath the Summit.

The Great Wave off Kanagawa, the best known print in the series

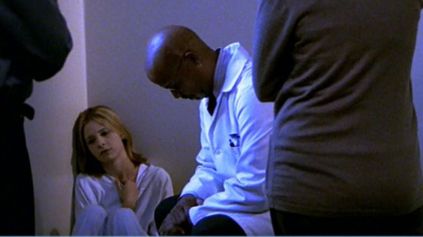

In the spirit of Hokusai, I thought I’d attempt something thematically similar: 25 critical and interpretative views (by various authors) of “Normal Again,” the 17th episode of season 6 of the television series Buffy the Vampire Slayer. This episode is a puzzlement: one of the most intriguing, haunting and baffling episodes of a show packed with stellar episodes. The episode is an alternate reality construct, a device used in half a dozen other TV shows over the years, including episodes of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, Charmed, The Sopranos, and Supernatural. It is especially haunting in that it appears to grant the “last word” to the reality of the alternate universe, apparently conceding that the entire show is actually a fantastic but unreal schizophrenic universe. This unsettling conclusion distinguishes the episode from other shows that have used the device, and drives most of the discussion about “Normal Again.”

“Normal Again” has been a challenge to those who write about the Buffyverse, as it defies almost all suppositions and preconceptions about the show. Even its authorship is odd: it bears many of the hallmarks of a Joss Whedon-penned (or perhaps a Marti Noxon) episode, but is actually attributed to Whedon’s personal assistant, Diego Gutierrez. This was Gutierrez’ first writing credit, and seems to have sparked his career: he has had a decent career since as a writer and producer, ranging from Dawson’s Creek to From Dusk Till Dawn. We should of course accept the credit at face value – as best we know, Gutierrez had a sensational writing debut, perhaps as part of a broader writing team contributing elements. This was a not-unusual regime on Buffy.

- “Buffy Summers (‘Normal Again’).” Buffyverse Wiki.

- “Normal Again.” Buffyverse Wiki.

- “Normal Again.” Wikipedia.

- “Recap: Buffy the Vampire Slayer S6E17 ‘Normal Again’.” TV Tropes.

- 6.17 Episode 117. “Normal Again.” Written by Diego Gutierrez. Directed by Rick Rosenthal. Air date: 12 Mar. 2002.

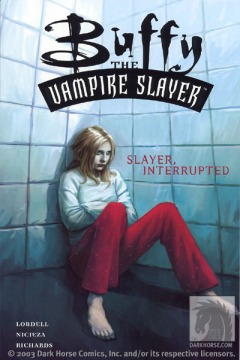

- Lobdell, Scott, and Fabian Nicieza. Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Vol. 16: Slayer, Interrupted. Dark Horse, 2003.

1. Whedon, Joss. “10 Questions for Joss Whedon.” New York Times 16 May 2003.

Q. 6. We hear you’re fond of Shakespeare’s works – “Hamlet” in particular. Could that have partly inspired the “Normal Again” storyline that Buffy might be insane, since one theory about “Hamlet” goes that the entire story is actually taking place in Hamlet’s imagination? How important is “Normal Again” in the “Buffy” arc?

A: I have never been a subscriber to, “the entire play takes place in Hamlet’s imagination” theory. In fact, although I’m a devoted fan of “Hamlet” and it is the text I know best in all the world, “Normal Again” did not come from it.

How important it is in the scheme of the “Buffy” narrative is really up to the person watching. If they decide that the entire thing is all playing out in some crazy person’s head, well the joke of the thing to us was it is, and that crazy person is me. It was kind of the ultimate postmodern look at the concept of a writer writing a show, which is not the sort of thing we usually do on the show. The show had merit in itself because it did raise the question, “How can you live in this world and be sane?” But at the same time the idea amused me very much and we played on it a little bit, “How come her little sister is taller than her?” “What was Adam’s plan?” We played on the crazy things we came up with time and time again, to make this fantasy show work and called them into question the way any normal person would. But ultimately the entire series takes place in the mind of a lunatic locked up somewhere in Los Angeles, if that’s what the viewer wants. Personally, I think it really happened.”

2. Noxon, Marti. Slayers & Vampires: The Complete Uncensored, Unauthorized Oral History of Buffy & Angel. Edward Gross and Mark A. Altman. Tor, 2017.

“It was a fake out; we were having some fun with the audience. I don’t want to denigrate what the whole show has meant. If Buffy’s not empowered then what are we saying? If Buffy’s crazy, then there is no girl power; it’s all fantasy. And really the whole show stands for the opposite of that, which is that it isn’t just a fantasy. There should be girls that can kick ass. So I’d be really sad if we made that statement at the end. That’s why it’s just somewhere in the middle saying “Wouldn’t this be funny if …?” or “Wouldn’t this be sad or tragic if…?” In my feeling, and I believe in Joss’ as well that’s not the reality of the show. It was just a tease and a trick.”

3. Rosenthal, Rick, and Diego Gutierrez. “Audio commentary by Director Rick Rosenthal and Writer Diego Gutierrez on ‘Normal Again’.” Buffy the Vampire Slayer: The Complete Sixth Season on DVD. Fox, 2004.

- Albright, Richard S. “‘Normal Again’: Alternate Realities.” Reading Joss Whedon. Ed. Rhonda V. Wilcox, et al. Syracuse UP, 2014. 93-95.

- Allrath, Gaby. “Life in Doppelgangland: Innovative Character Conception and Alternate Worlds in Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Angel.” Narrative Stategies in Television Series. Ed. Gaby Allrath and Marion Gymnich. Palgrave Macmillan, 2005. 132-50.

- Croft, Janet Brennan. “‘What if I’m still there? What if I never left that clinic?’: Faërian Drama in Buffy‘s ‘Normal Again’.” Slayage: The Journal of Whedon Studies 48 (Summer/Fall 2018).

- “Episode Analysis: ‘Normal Again‘.” Linda’s Buffy Stuff.

- Flor, Chris, and Philipp Kneis. “‘Normal Again’: Buffy the Vampire Slayer as Psychotic Narration.” Picturing America: Trauma, Realism, Politics, and Identity in American Visual Culture. Ed. Antje Dallmann, et al. Peter Lang, 2007. 65-77. In “Normal Again” (6.17), Buffy exists in our real world, hospitalized as a schizophrenic struggling to return to sanity. The episode questions the validity of the Buffyverse that the audience has come to accept. Buffy is part of a long tradition of “psychotic narratives” such as Brazil, 12 Monkeys, The Truman Show, and The Manchurian Candidate. The authors contend that the show functions as a schizophrenic delusion.

- Geller, Len. “‘Normal Again’ and ‘The Harvest’: The Subversion and Triumph of Realism in Buffy.” Slayage: The Journal of Whedon Studies 32 (Winter 2011).

- Gobatto, Nancy. “‘Ready to Be Strong?’: Buffy, Angelina, and Me.” Girls Who Bite Back: Witches, Mutants, Slayers and Freaks. Ed. Emily Pohl-Weary. Sumach, 2004. 119-31. Gobatto was very much affected by the Buffy episode “Normal Again” (6.17), with its transgressive suggestion that Buffy’s whole life was entirely delusional. She was stunned by the episode, and explored the story further in the comic book Slayer Interrupted, which expanded on Normal Again. She believes that in both stories “the notion of insanity becomes an excuse to resist strength and responsibility.”

- Harper, Stephen. “Dark Fears: Madness in Gothic and Supernatural Drama.” Madness, Power and the Media: Class, Gender and Race in Popular Representations of Mental Distress. Palgrave Macmillan, 2009. 115-16. Madness appears as a motif in a number of television series, including Smallville, Medium, the British show Afterlife, and Buffy. Stephen Harper looks at “Normal Again” as an example. He thinks the episode exemplifies Buffy’s fear of parental rejection, as well as a romantic subtext of her feelings for Spike.

- Hessel, Stephen. “Horrifying Quixote: The Thin Line between Fear and Laughter.” Fear Itself: Reasoning the Unreasonable. Ed. Stephen Hessel and Michèle Huppert. Rodopi, 2009. 34-35. Any situation can become terrifying when one is unsure where things stand: when vampires can be human, and when good people can do monstrous things. Buffy has to navigate by rules that prove inadequate. This is stunningly brought home in “Normal Again”, when all the rules are obliterated, and Buffy is left with few guidelines about reality.

- Jagodzinski, Jan. “The Death Drive’s at Stake: Buffy the Vampire Slayer.“ Television and Youth Culture: Televised Paranoia. Palgrave Macmillan, 2008. 111-32. Jagodzinski reiterates the Hero’s Journey that Buffy encompasses, but considers it “completely inverted.” There is no jumping around between worlds, and Buffy’s Guides are incompetent. However “Normal Again” raises the haunting possibility that Buffy is a schizophrenic. This episode came “dangerously close to exposing…the secret of the Buffyverse narrative.” The episode strips away the psychic structure of the series itself, opening a porthole into its inner workings.

- Mains, Christine. “‘Dreams Teach’: (Im)Possible Worlds in Science Fiction Television.” The Essential Science Fiction Television Reader. Ed. J. P. Telotte. Lexington: UP of Kentucky, 2008. 143-58. Examines the common trope in science fiction television, in which a character enters an alternate reality that is much more real than the fantastic world that they regularly inhabit. In Buffy, this is “Normal Again” (6.17). In the end, the character has to make a choice: whether to return to the heroic life, even though “normal” life may be temptingly free of danger and pain. Buffy chooses to return to the “fictional” world of Sunnydale. This is entirely necessary; however, writer Diego Gutierrez famously plays with the audience by “the power of the last word.” In the final scene, the doctor shines a light into Buffy’s dead eyes, intoning that she is catatonic forever, while her distraught parents weep for their lost daughter. The audience is left with the haunting question: what is “real”?

- Miller, Craig. “Is Buffy ‘Normal Again’?” Review of the Buffy episode ‘Normal Again’.” Spectrum 32 (Nov. 2002).

- Murray, Noel. “Buffy/Angel: ‘Normal Again’/’Forgiving‘.” AV Club 4 Mar. 2011. “My wife Donna doesn’t see it that way. She shrugged off the implications of the ending, saying that to her it wasn’t that important. To her, what matters is that Buffy made a conscious choice. Buffy had to wrestle with where she’d rather be, and she chose Sunnydale and her friends. If her delusions were purely and clearly demonic in origin, that choice would’ve been meaningless. Instead, by showing both realities as viable, the writers make Buffy’s choice to stay in Sunnydale a significant one. This wasn’t her being dragged back from ‘heaven’ against her will. This was her saying, ‘This is my home.’ I like that reading. I wish it had been dramatized more effectively – maybe in a Last Temptation Of Christ ‘getting back on the cross’ kind of way – but in the larger arc of this season, it fits with Buffy’s growing awareness that she needs to get out of her own head and start taking care of the people around her.”

- “‘Normal Again’: The Buffyverse’s Greatest Debate.” r/buffy Reddit.

- Pateman, Matthew. “Chapter 1: Aesthetics, Culture and Knowledge: ‘Everyone Forgets, Willow, That Knowledge Is the Ultimate Weapon.'” The Aesthetics of Culture in Buffy the Vampire Slayer. McFarland, 2005. 15-37. Covers the role and function of knowledge within the Buffyverse. Knowledge is distributed in different ways throughout the series, and this drives the narrative. From the very beginning, the core Scooby group is formed with secret knowledge of another world, and Buffy’s momentous function within that world. The audience shares in the intimate knowledge of the “true” world, while conventional Sunnydale carries on in blissful ignorance. But in the complex world of Buffy, a number of episodes disrupt this duality, especially “Normal Again”.

- Peeling, Caitlin, and Meaghan Scanlon. “‘What’s more real? A sick girl in an institution… Or some kind of supergirl’: The Question of Madness in ‘Normal Again’: A Feminist Reading.” Slayage Conference on Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Nashville, TN, May 27-30 2004.

- Rose, Susanne. “Nothing Normal about the Monsters: Postmodern Monstrosity in Buffy the Vampire Slayer‘s ‘Normal Again’.” Watcher Junior 9 (June 2014).

- Stevenson, Gregory. “Chapter 3: Storytellers.” Televised Morality: The Case of Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Hamilton, 2003. 23-42. What is the point of the story? Whedon points out that the stories of Buffy are “fairytales, not driving manuals.” We tell ourselves and our children stories in order to make sense of our lives. Fantasy stories are more than just escapism, but a way to represent emotional reality. Stevenson examines three episodes that illustrate this maxim: “Superstar” (4.17), “Normal Again” (6.17), and “Storyteller” (7.16). When Buffy fights monsters, she is trying to replace chaos with order, to create a better world even though the world tends to resist.

- Wilcox, Rhonda V. “The Aesthetics of Cult Television.” The Cult TV Book. Ed. Stacey Abbott. Tauris, 2010. 31-39. Print. Wilcox notes that a basic feature of the cult TV audience is their attentiveness to the text. She discusses aesthetic elements such as music, visual techniques, lighting and color palettes, narrative seriality, and culturally significant symbolism. Another aesthetic characteristic is provided by parallel universes and time distortions, and “Normal Again” is singled out as “the most metatextually unnerving of the parallel universes.”